In Puerto Rico, where both Spanish and English are now co-official languages, the new school year has begun and with it comes the start of the commonwealth’s new bilingual education program. Starting yesterday, math and science in 32 different pilot schools will switch to being taught in English. Visit Hispanically Speaking News to find out why the switch is underway and why not everyone is in favor of the change.

Linguistic Link: Learn to Speak Colbertian

It is common for researchers to use artificial languages to test certain aspects of language acquisition. Linguists at Northwestern University cleverly took it one step further by referencing the world of pop culture with their made-up language, naming it after satirist Stephen Colbert, a man known for humorously coining his own words, such as ‘truthiness’. Colbertian was used to test whether being bilingual aids in learning another language, which the researchers say it does. You can read more of the details in the Chicago Sun-Times write-up. Furthermore, you can even learn Colbertian yourself!

It is common for researchers to use artificial languages to test certain aspects of language acquisition. Linguists at Northwestern University cleverly took it one step further by referencing the world of pop culture with their made-up language, naming it after satirist Stephen Colbert, a man known for humorously coining his own words, such as ‘truthiness’. Colbertian was used to test whether being bilingual aids in learning another language, which the researchers say it does. You can read more of the details in the Chicago Sun-Times write-up. Furthermore, you can even learn Colbertian yourself!

Linguistic Link: Bilingual Benefits for Deaf Children

A new study from La Trobe University highlights yet again the importance of bilingualism from a young age. The same way that early exposure to multiple languages increases cognitive abilities in hearing children, exposure to both spoken and sign language for deaf children has positive effects on cognition and language learning. Check out this article for more details.

While you’re at it, feel free to increase your own bilingual abilities by taking a moment to learn some basic greetings in British Sign Language (BSL), which was the sign language focused on in the study.

Linguistic Link: Bilingual TV

NPR has an interesting report on the growing trend of producing bilingual Spanish/English television programs here in the US. Although they may be following in the footsteps of the successful bilingual children’s cartoon Dora the Explorer, this new trend is not just for children. Importantly, nor is it just for bilinguals, as they mention the programs are subtitled in both Spanish and English for those less dominant in one language or the other. Listen to the story and check it out for yourself.

NPR has an interesting report on the growing trend of producing bilingual Spanish/English television programs here in the US. Although they may be following in the footsteps of the successful bilingual children’s cartoon Dora the Explorer, this new trend is not just for children. Importantly, nor is it just for bilinguals, as they mention the programs are subtitled in both Spanish and English for those less dominant in one language or the other. Listen to the story and check it out for yourself.

Linguistic Link: What Do Linguists Do?

Literacy News has a great litle blurb on a question all of us get on a regular basis: What do linguists do? Although it mentions a wide-variety of the avenues available in the linguistics field profession-wise, it does make clear a common misconception. That is, being a linguist does not mean that you are “fluent in five languages and spend your day thumbing through dictionaries.”

Literacy News has a great litle blurb on a question all of us get on a regular basis: What do linguists do? Although it mentions a wide-variety of the avenues available in the linguistics field profession-wise, it does make clear a common misconception. That is, being a linguist does not mean that you are “fluent in five languages and spend your day thumbing through dictionaries.”

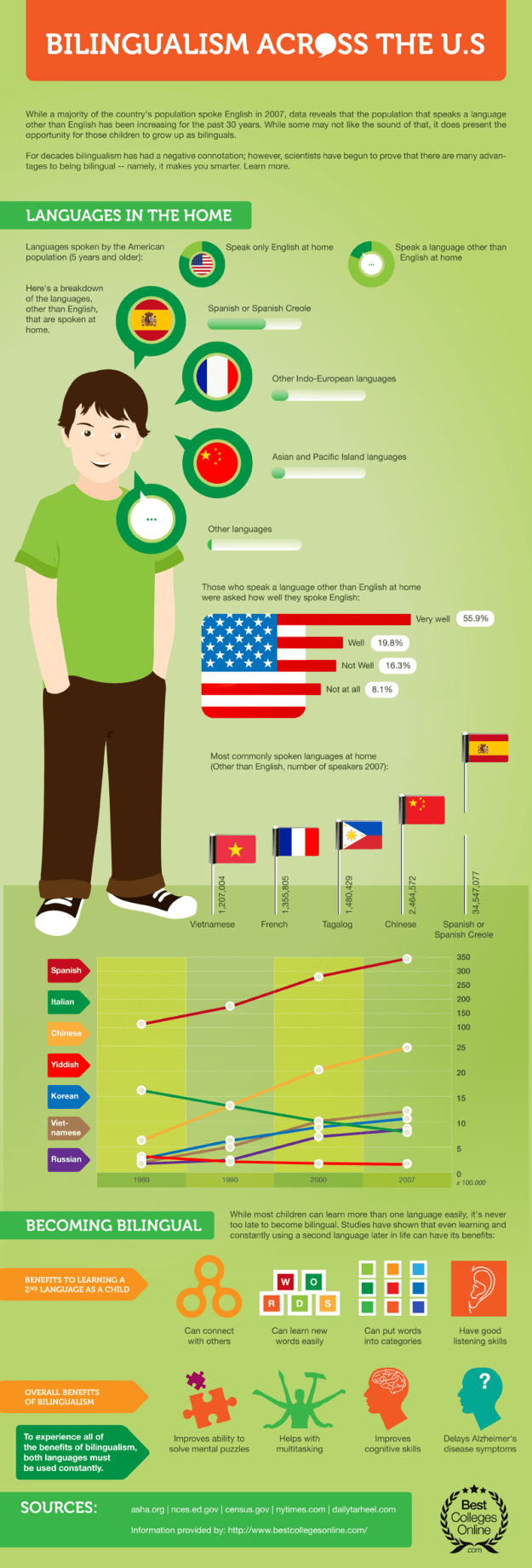

Linguistic Link: Bilingualism in the US

Best Colleges Online recently published an infographic about Bingualism in the US. Check it out.

Linguistic Link: Clever Apes on Bilingualism

Chicago public radio station WBEZ 91.5’s Clever Apes focused on bilingualism recently. Be sure to check out their segment which highlights the benefits of being bilingual. It also includes an interview with Dr. Boaz Keysar from the University of Chicago who studies language and decision making.

Chicago public radio station WBEZ 91.5’s Clever Apes focused on bilingualism recently. Be sure to check out their segment which highlights the benefits of being bilingual. It also includes an interview with Dr. Boaz Keysar from the University of Chicago who studies language and decision making.

UIC TiL: Marcel den-Dikken

Greetings everyone!

Next Monday April 23th Marcel den-Dikken from CUNY will be giving a talk at UIC Talks in Linguistics (UIC TiL) entitled ‘Of orphans and twins: Accounting for some peculiar patterns in code-switching’ (see abstract below).

The talk will take place in University Hall 1501 at 3 pm, and as always, light snackswill be provided.

Of orphans and twins: Accounting for some peculiar patterns in code-switching

González-Vilbazo & López (2012) note that in Spanish/German code-switching (CS) a switch at v from a Spanish light verb (inserted in v) to a VP lexified by German vocabulary items leads VO order thanks to the fact that the Spanish v dictates the syntax of the vP (see (1a), analysed as in (1b)). But they also point out that there are speakers for whom the Spanish v=hacer can be followed by a German VP with (German) OV order (as in (2a)). They argue that constructions of the type in (2a) involve what they call an ‘orphan’: a chunk of structure that is not integrated with the rest of the structure of the clause in the regular fashion. The analysis for (2a) that they propose is schematised in (2b), a structure in which there are two vPs, one from Spanish (spelled out as hizo) and the other from German (which is silent); it is the German v that takes the overt VP as its complement, and which causes the VP to be spelled out with (German) OV order.

(1) a. Juan hizo verkaufen die Bücher Juan did sell the books

‘Juan sold the books’

b. [vP vSp=hizo [VP verkaufen die Bücher]](2) a. Juan hizo die Bücher verkaufen Juan did the books sell

‘Juan sold the books’b. [vP vSp=hizo (…)] [vP [VP verkaufen die Bücher] vGe=i]]

González-Vilbazo & López point out that CS constructions with ‘orphans’ such as (2a) behave differently from run-of-the-mill Sp/Ge CS constructions such as (1a) with respect to a number of syntactic properties, including extraction (Worüber has hecho {Tlesen ein Buch/*ein Buch lesen}? ‘about what have you read a book’) and anaphoric dependencies (Juan se ha hecho {Tsehen sich selbst im Spiegel/*sich selbst im Spiegel sehen} ‘Juan saw himself in the mirror’). The ‘orphan’ status of the second vP in (2b) straightfor- wardly explains the fact that nothing can be extracted out of it. But as it stands, the proposal in (2b) leaves two things unexplained: (a) why the object of the OV-VP cannot be anaphorically bound to the subject of the clause, and (b) how the ‘orphan’ relates to the ‘(…)’ in the complement of the non-orphaned v, and what the nature of ‘(…)’ might be.

The problem with (a) is that, since the ‘orphaned’ constituent must be a vP in order for the German v to be able to dictate OV order inside it, and since vP is the locus of base-generation of the external argu- ment, it ought to be possible for the ‘orphaned’ vP in (2b) to have a (null) subject of its own, coreferential with the subject of the clause; an anaphor inside VP should then be able to be locally bound by the null external argument of the ‘orphaned’ vP, and binding should succeed. We will want to make sure that, even though the ‘orphaned’ constituent must indeed be a vP (for word-order purposes), it cannot house an instance of the external argument.

I propose to ensure this by analysing the ‘orphan’ as an asyndetic specifier of the first vP, in a covert coordination structure of the type proposed in work by Koster (2000 et passim). This is a case of asyndetic coordination at the level of vP minus the external argument, which is merged outside the coordinate structure, and introduced by a relator that has the shared external argument as its specifier and the asyndetic coordinat- ion (annotated as ‘:P’, following Koster) as its complement, as in (3).

(3) [RP Juan [RELATOR [:P [vP1 vSp=hizo [VP ec]] [: [vP2 [VP die Bücher verkaufen] vGe=i]]]]]

Coordination/asyndetic specification must be at the level of vP because coordination of acategorial constituents (‘VP’) is impossible; moreover, vP must be present in the second conjunct in order to case- license the object of the German verb. But there is no need to introduce the external argument inside the individual conjuncts: having it be introduced by a relator outside the coordination is derivationally simpler because it involves fewer instances of External Merge (the external argument is merged just once, not twice) and it avoids Across-the-Board extraction of the external argument from the two conjuncts in parallel. (3) is thus the most economical structure for the ‘orphan’ construction — and moreover, it gives the ‘orphan’ an important function: it serves to specify the contents of the empty VP in the first conjunct.

An elliptical VP in the first conjunct thus fills in the ‘(…)’ in the structure in (2b). It must be an empty category because a multi-dominance approach to ‘orphan’ constructions is impossible: having the VP dominating die Bücher verkaufen attached simultaneously to the empty German v and to the Spanish v spelled out as hizo would impose irresolvably conflicting word-order demands upon the VP: since VP would serve simultaneously as the complement of a German and a Spanish v, the object inside VP would have to simul- taneously precede and follow the verb, which is of course impossible. For this kind of Right Node Raising, therefore, an analysis in terms of multi-dominance is out of the question.

Represented this way, the ‘orphan’ construction becomes an instance of a much broader pattern observed in CS constructions: so-called doubling. (2a) is in effectively a doubling construction: the v+VP part of the structure occurs twice, and v is spelled out in both conjuncts — albeit as a null morpheme in the second conjunct, which makes (2a) hard to recognise as a doubling construction. More readily recognisable doubling constructions are utterances such as those in (4), from English/Tamil CS (taken from Sankoff et al. 1990:93).

(4) a. verb doubling

they gave me a research grant ko`utaa

they gave me a research grant gave.3.PL.PAST ‘they gave me a research grant’b. auxiliary+verb doublingI was talking to oru orutanoo`a peesin`u irunteinI was talking to one person talk.CONT be.1.SG.PAST ‘I was talking to a person’c. complementiser doubling

just because avaa innoru colour and race engindratunaale just because they different colour and race of-because

‘just because they are of a different colour and race’I analyse all cases of doubling in CS as involving asyndetic specification, with the ‘shared’ constituent sandwiched between the doublets being the asyndetic specifier of an elliptical constituent in the first conjunct (as in (3)).

Doubling is by no means confined to CS — hence is not a ‘CS-specific’ phenomenon that would justify a separate ‘grammar of CS’. Doubling is found in utterances of monolingual speakers as well. An example occasionally discussed in the literature is complementiser doubling in sentences of the type in (5a) (from Spanish) and (5b) (from Dutch). These constructions are sometimes treated as cases of CP recursion or CP–TopP structures (the latter with a Top-head spelled out as a complementiser) in a strictly right- branching structure. I will present evidence, however, for the conclusion that these are, just like the construc- tions reviewed above, instances of asyndetic specification, with an elliptical TP in the first conjunct. Spanish and Dutch complementiser doubling in addition makes a case for the conclusion that the elliptical TP is a base-generated empty category (ec in (3)), not a PF-deleted full-fledged TP: the sandwiched topic must be base-generated in situ, and can never be followed (in a non-doubling construction) by a non-elliptical TP.

(5) a. dice que dinero que no teníasays that money that not had‘(s)he says that (s)he didn’t have money’b. ik denk dat van brood alleen dat je daarvan niet kunt leven I think that of bread alone that you thereof not can live ‘I think that one can’t live on bread alone’

Video: Stephen Fry Kinetic Typography-Language

Does the incorrect usage of grammar bug you? Do you know the difference between disinterested and uniterested?

Check out this video about a point of view towards the use or mis-use of language today.

UIC TiL: Brady Clark

UIC Talks in Linguistics invite you to the next TiL this Friday the 13th.

Brady Clark from Northwester will be leading the talk entitled ‘Syntactic theory and the evolution of syntax’

As always, the talk will take place at UH 1750 at 3pm.

Again, this Friday April 13 at 3pm.

Here is an abstract of the talk,

Brady Clark

Northwestern UniversityContemporary work on the evolution of syntax can be roughly divided into

two perspectives, the incremental view and the saltational view. The

incremental view claims that the evolution of syntax involved multiple

stages between the noncombinatorial communication system of our last

common ancestor with chimpanzees and full-blown modern human syntax. The

saltational view claims that syntax was the result of just a single

evolutionary development. What is the relationship between contemporary

theories of syntax and these two perspectives on the evolution of syntax?

Jackendoff (2010) argues that there is a dependency between theories of

language and theories of language evolution: “Your theory of language

evolution depends on your theory of language.” For example, he claims that

most work within the Minimalist Program (for background, Chomsky 1995) is

forced to the saltational view. My focus in this talk is the evolution of

syntax, and, in particular, the relation between syntactic theory and

perspectives on the evolution of syntax. I argue that there is not a

simple dependency relation between theories of syntax and theories of

syntactic evolution. The parallel architecture (Jackendoff 2002) is

consistent with a saltational theory of syntactic evolution. The

architecture assumed in most minimalist work is compatible with an

incremental theory.

See you there!